Dr. Buhezo describes the ‘Heart Without Borders’ campaign as rewarding.

11 April, 2025

Hugo Buhezo, one of the cardiologists who participated in the “Corazón sin Fronteras” campaign, describes the experience with his colleagues as rewarding. “For those people, we are now like rock stars; everyone asks us for photos (laughs),” he jokes. “Seeing the expressions of joy on people’s faces when they learn they’ve been selected and won’t have to pay anything for the new lease on life they’ll receive is incredibly moving.”

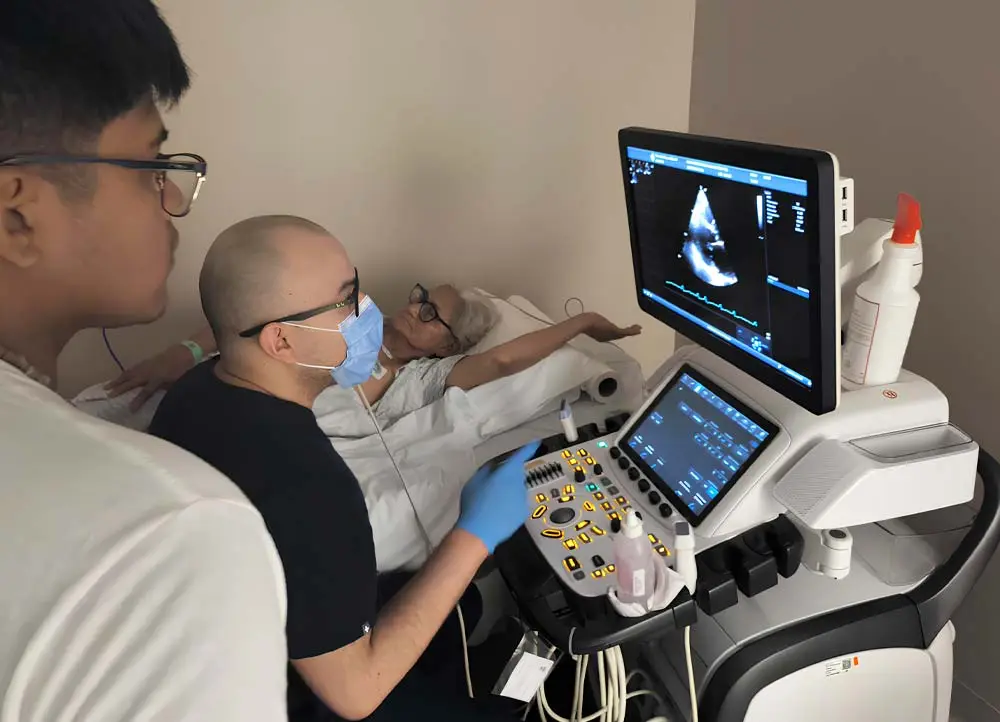

It has been two weeks since 30 people received pacemakers in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, and according to the doctors monitoring them, “thank God, everything is going well.” These procedures were carried out as part of the “Corazón sin Fronteras” campaign, organized by the Nacional Vida Segura Foundation, the Clínica de las Américas, and the Universidad Autónoma Gabriel René Moreno.

Cardiologists Hugo Buhezo, Javier Moro, and Gustavo Durán were part of this health initiative, working alongside a team of doctors from Project Pacer International, a U.S.-based organization dedicated to providing cardiac therapy to underprivileged patients. This marked their second collaboration; in 2023, they installed 23 pacemakers together.

The “Corazón sin Fronteras” campaign featured four types of devices donated to Project Pacer International by the companies Biotronik and Medtronic: the VVI, which affects only the atrium or ventricle; the DDD, which acts on both the atrium and ventricle; the CDI, which functions as a defibrillator; and the TRC, which is biventricular.

Project Pacer International is a nonprofit organization focused on delivering modern cardiac therapies to low-income patients in developing countries. For the beneficiaries, acquiring these devices was unattainable. Most of them came from rural areas, including provinces in Chuquisaca. The cost of a VVI is around $2,500, a DDD $3,000, a CDI $10,000, and a TRC or resynchronizer $20,000. This does not include implantation costs, medical fees, or hospitalization expenses.

Despite their desire to improve their quality of life and live many more years, some patients did not hide their fears. However, professionals consider this a normal reaction and address it by explaining that these are minimally invasive, outpatient procedures. The devices, about half the size of a computer mouse, are implanted under the skin near the left clavicle and connected to the heart through veins.

Approximately 200 people applied to benefit from the campaign, many from Bolivia’s Chaco region and diagnosed with Chagas disease. Project Pacer International evaluated candidates based on medical studies submitted and diagnoses recommending pacemaker use. After assessing the urgency of their cases and their economic situations, 30 patients were selected. The type of device implanted depended on each patient’s specific needs.

Follow-up consultations will continue until September. Each pacemaker can be remotely monitored from the clinic using specialized computers, but patients must attend periodic checkups, bringing their implant identification cards. “They are happy; they have a new lease on life,” says Dr. Buhezo.